An ambitious new book traces the rise, fall and resurrection of the Central West End, the historic neighborhood near Washington University Medical Campus. “Renaissance: A History of the Central West End” is a 320-page coffee table book written by St. Louis author Candace O’Connor and published by Reedy Press.

Impetus for the book came from William H. Danforth, MD, university chancellor from 1971 to 1995 and former vice chancellor for medical affairs. Danforth said he felt it was important to highlight the medical center’s crucial role in saving its own neighborhood and staying in the city even as crime escalated and the area faltered.

Impetus for the book came from William H. Danforth, MD, university chancellor from 1971 to 1995 and former vice chancellor for medical affairs. Danforth said he felt it was important to highlight the medical center’s crucial role in saving its own neighborhood and staying in the city even as crime escalated and the area faltered.

O’Connor has written extensively on the history of the university and the medical center. Among many others, her books include: “Beginning a Great Work: Washington University in St. Louis, 1853–2004,” “A Surgical Department of Distinction: 100 Years of Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine,” “Imaging & Innovation: A History of Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology,” “Hope and Healing: St. Louis Children’s Hospital,” and the forthcoming “A Legacy of Caring: The History of Barnes-Jewish Hospital.”

Here, O’Connor answers questions related to her new book on the Central West End:

WELLS FARGO

WELLS FARGOWhat was the Central West End like before the School of Medicine was built?

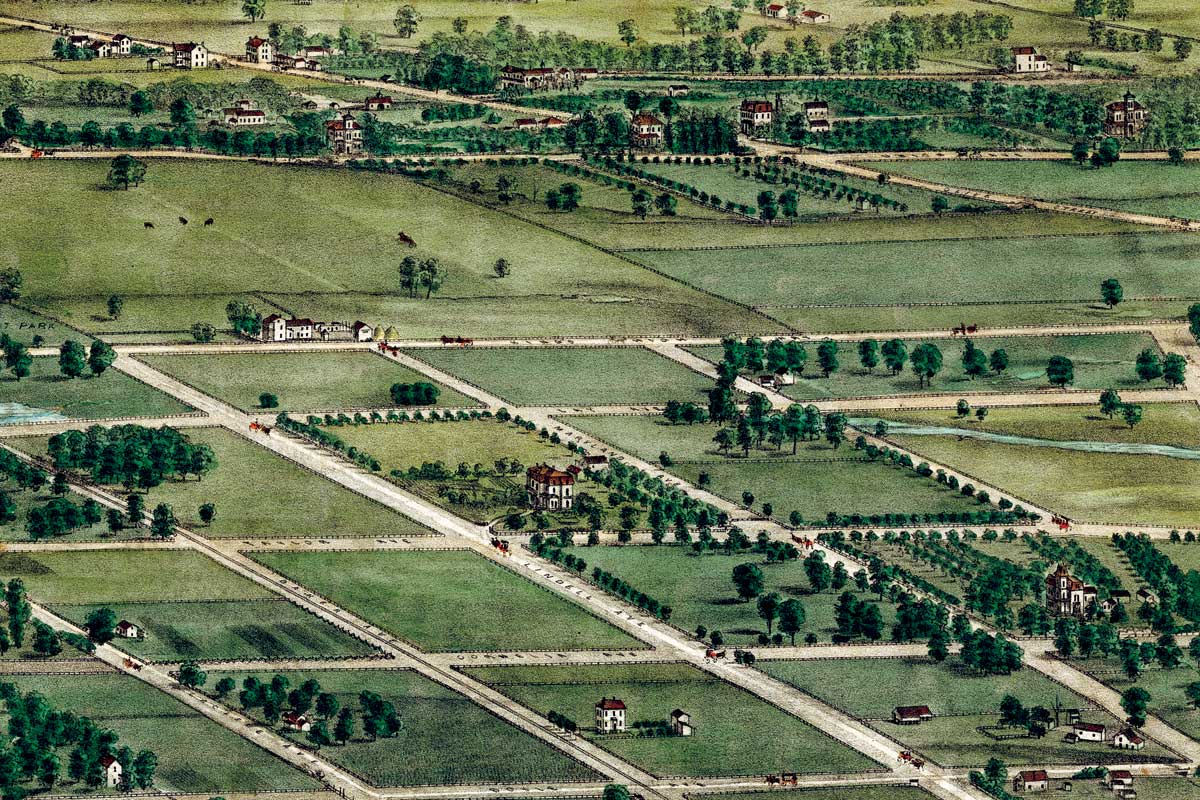

By the time the new Washington University School of Medicine campus was dedicated in 1915, the Central West End (CWE) was by far the most desirable neighborhood in St. Louis. In 1875, when Compton and Dry created their famous bird’s-eye views of the city, the CWE had been a sleepy, rural place, mostly farmland. But in the run-up to the 1904 World’s Fair, and in the booming years afterward, that changed dramatically. High-end builders developed beautiful streets, including private places, along with chic commercial districts. Robert Brookings, the university board chairman who moved the medical school from downtown St. Louis to Kingshighway, bought a home for himself on Lindell, across from Forest Park. Religious congregations moved in, as did other hospitals. Many of the city’s elite settled in CWE houses, including such noted School of Medicine physicians as Washington Fischel, George Gellhorn, W. McKim Marriott, Evarts Graham and Vilray Blair. A 1912 book, published by a local newspaper, listed the 4,000 most famous men in St. Louis — and most of them lived in the CWE.

As the medical school and its affiliate hospitals grew and prospered, what was happening in the neighborhood around it?

During the teens, 1920s and into the 1930s, the CWE flourished. Prominent people, such as David Francis — who was chief World’s Fair organizer, St. Louis mayor, Missouri governor and ambassador to Russia — lived in giant houses, staffed by uniformed servants. At Kingshighway and Lindell, the William Bixby family owned the entire block and lived in a palatial home that later was demolished to make way for the elegant Chase and Park Plaza hotels.

When and why did the downturn in the neighborhood begin?

In 1927, a powerful tornado devastated parts of the CWE, killing 78 people and injuring 500. On many days, a pall of smoke, caused by coal fires and industrial pollution, hung over the area, and some residents began to look toward new suburbs with cleaner air. During the 1930s-era Depression, some of the large homes became unaffordable. Then at the end of World War II, the crush of returning soldiers created a huge demand for housing. Suddenly, owners had a great incentive to break up these large homes into rooming houses. In the 1950s and 1960s, some mansions were torn down for modern high-rises or even parking lots.

What was the Central West End’s low point?

By the 1960s and early 1970s, the situation in the CWE had become critical. As Dr. Ron Evens (former head, Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, and former president, Barnes-Jewish Hospital) said: “People don’t realize when you go to the CWE now, what it was like then. It was seedy. It was dirty. It was high crime. It was prostitutes. It was people drunk on the streets. So the issue became, ‘Oh, my God, what are we going to do about that?’” Dr. Will Ross (nephrologist and associate dean) said that when he was here for a medical school interview, he was walking down Kingshighway when a policeman behind him began shooting at a man in front of him. In 1962, the medical center institutions banded together, forming the organization later called the Washington University Medical Center. Still crime was a serious problem for employees, who were being robbed on the streets. Other hospitals — St. John’s, Shriners, Missouri Baptist and St. Luke’s — started moving out of the area.

What did Washington University Medical Center do about it?

During the 1960s, Dr. William Danforth, then vice chancellor for medical affairs, began to worry about the flight of these hospitals and the fancy new “Palaces on Ballas” they were building in the western suburbs. He tapped the talented young Dr. Evens to head a committee that would consider three options: move the medical center west, stay put, or remain in place but build a clinical presence in the Plaza Frontenac area. Raymond Wittcoff (developer and Jewish Hospital board member) was a major advocate for staying in the city, and ultimately that view prevailed. Next Wittcoff contacted an architectural firm to design a plan for the Central West End. But the proposal called for razing a huge swath of the area — and somehow it was leaked to a local newspaper. People living in the neighborhood, who were working hard to save it, were horrified.

“That decision (to stay) may be one of the five most important decisions ever made in terms of the history of the city of St. Louis. Because if the Washington University Medical Center had left … can you imagine what the city of St. Louis would be like?” — Jerry King

What did the medical center try next?

They needed a new approach. So Dr. Danforth, who became university chancellor in 1971, had lunch with developer Richard Roloff, then working for Capitol Land Company, and he generously agreed to take on volunteer leadership of a new revitalization effort. He did a spectacular job, though it was tough going. At his first meeting with residents, he encountered a crowd still angry from the newspaper article. As he recalled, every one of those people would cheerfully have bought him a one-way ticket to California! But he persisted, hiring urban design firm Team Four to devise a plan that would save as much historic architecture as possible, acquire homes from residents ready to leave and re-sell them to young buyers, eager to renovate. He and his team also brought in a major client, Blue Cross, to new headquarters that later became the 4444 building on Forest Park Avenue.

How successful was this revitalization effort?

It was extraordinarily successful. The Washington University Medical Center Redevelopment Corporation (WUMCRC) — headed successively by executive directors Jerry King, Eugene Kilgen and others — worked in partnership with area residents and the medical center, particularly psychiatrist Dr. Samuel Guze, who succeeded Dr. Danforth as vice chancellor for medical affairs. They bought up dilapidated homes, such as those on the 4300 and 4400 blocks of Laclede; often the elderly owners would greet them at the door and say gratefully, “Where do I sign?” Then they attracted young families — even the new superintendent of the St. Louis schools — to buy and rehab them. A diverse group of people moved in. They also encouraged new businesses to come in. Of course, the medical school and the hospitals have since thrived and grown substantially, with more than 20,000 people working there daily. One surprise has been that the WUMCRC, initially viewed as a decade-long effort, continues today under executive director Brian Phillips. The CWE now is a vibrant mix of historic buildings and new development.

How does the future look for the Central West End and surrounding neighborhoods?

The future of the CWE is very bright, and its success also has been a catalyst for growth in other neighborhoods. The Forest Park Southeast area, now known as The Grove, began a major renewal under the leadership of William Peck, then dean of the medical school, and Dr. Jerry Flance, who worked with residents and urban pioneers. And the new Cortex Innovation Community, a 200-acre technology district to the east, developed there in part because startup businesses liked the proximity to the medical center and to the diverse, exciting CWE. Today, Cortex is one of the fastest growing technology startup scenes in the U.S., with more than 250 companies on site. So the WUMCRC’s valiant efforts in the 1970s and beyond have certainly had a wide-reaching impact.

“I hope that St. Louisans and people from surrounding areas will continue to cooperate to improve their home region with concern for the whole instead of just their own piece of turf. If so, I foresee a great future for us all.” — William Danforth